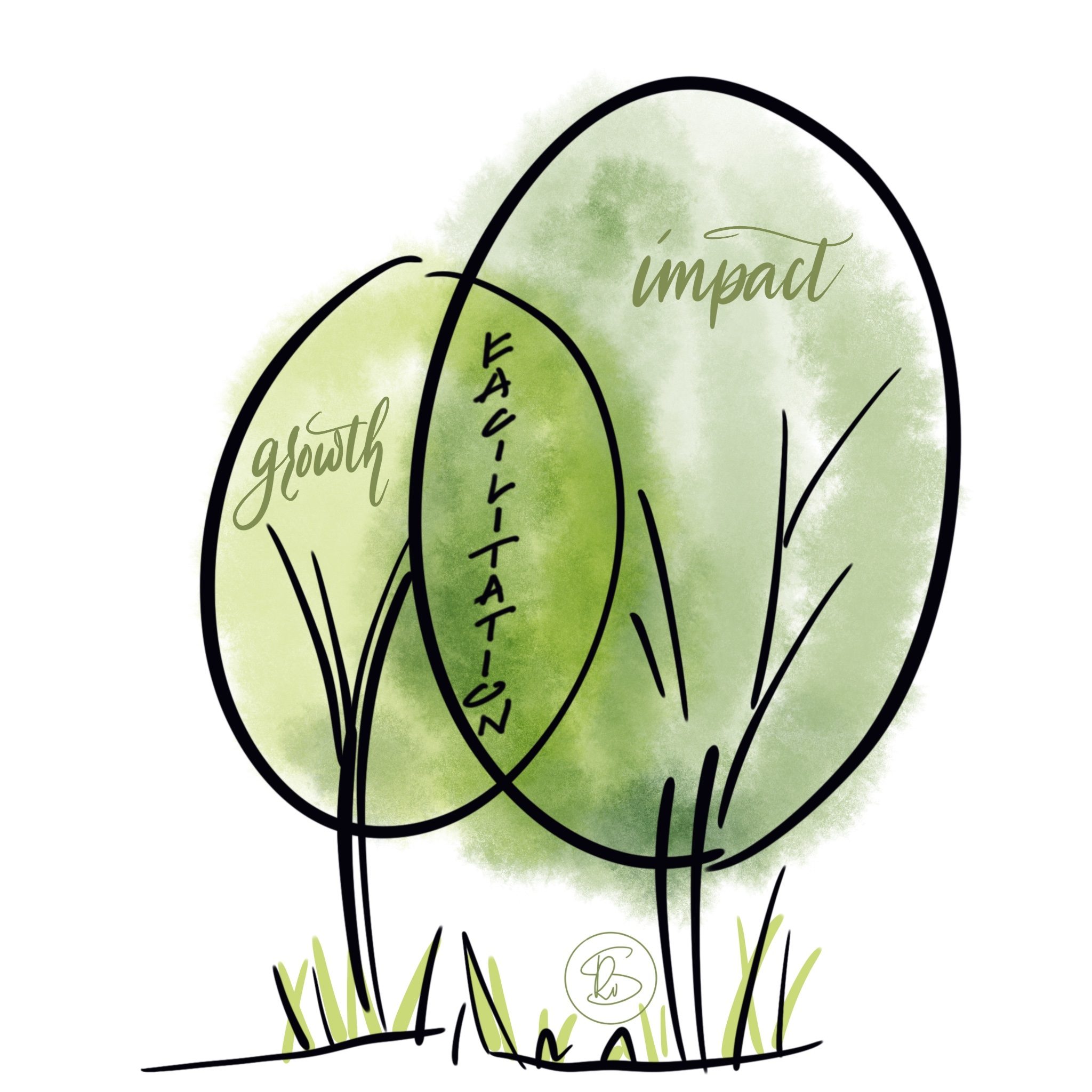

This chapter focuses on the power of facilitation as an enabler of positive public dialogues and critical conversations and as a tool to resolve conflicts. The power of facilitation can help leaders, managers, community advocates, public dialogue professionals, mediators, facilitators and anyone who is faced with conflict. It helps to resolve disputes between individuals or within/between groups in a productive, positive and sustainable manner.

Engaging individuals, groups or the public in resolving disputes or wicked problems is not about choosing between options or debating choices, it is about dialogue, conversations and problem solving.

Engaging individuals, groups or the public in resolving disputes or wicked problemsi is not about choosing between options. It is not about debating choices. It is about dialogue. It is about conversations. And it is about problem solving. As we have explored in previous chapters, the power of facilitation enables individuals and groups to communicate effectively. It helps people better understand themselves and each other. And it helps people think critically about solutions that can resolve the conflict. This chapter will examine how the power of facilitation can help to create a positive and sustainable resolution to any conflict. Whether the conflict is between individuals, within or between groups or across society, the power of facilitation can help.

When people gather physically, virtually or spiritually, there are bound to be disagreements. The question is: will the disagreements lead to destructive outcomes or constructive ones? Conflict is a normal part of life. Creativity, growth, innovation and learning all need some conflict in which to occur and thrive. In his book Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration, Ed Catmull describes the key role that Pixar’s Braintrust had in creating their successful movies. Catmull claims their success was a result of fostering creativity through candour. It encouraged debate and examination of all points of view and differences of opinion.

Scientists have used the double-blind peer review process to improve the quality of their research for decades. This process allows them to challenge their own theories, assumptions and methodologies to strengthen their logic and conclusions. As far back as the fifth century BC, democratic societies have used various forms of debate. This dialogue method was designed to ensure public decisions are well thought out. It was also designed to promote logical decisions that were in the best interests of the society they serve.

Constructive conflict has been proven through the centuries as an effective tool to foster innovation, creativity and consensus building. Yet, many of us still view conflict as a destructive force. Mary Parker Follett is often quoted as saying, “All polishing is done by friction.” How can we harness the power of facilitation to help us to ensure that friction polishes rather than destroys human relationships? How can we help individuals, groups and societal factions to embrace the notion of constructive conflict? How do we move from “beat and defeat” to “together we can”?

The Vacuum Monster

If necessity is the mother of invention, conflict is its father

Kenneth Kaye

In 350 AD, Greek philosopher Aristotle coined the phrase, “Nature abhors a vacuum.” This is based on the principle that nature requires every space to be filled with something. This is why, when you place an empty container in a sink full of water, the water rushes in to fill the empty space. This theory of the physical universe can help us explain why conflict happens and how to guide the conflicting parties towards constructive outcomes.

Let’s take a typical office example of a conflict situation. Group A makes a seemingly trivial decision to move the water cooler. Group B begins talking among themselves: “Why was the water cooler moved?”, “Why to that spot?”, “Did they do that so they could spy on us when we chat at the cooler?” And on it goes. Next thing you know tensions rise, suspicions start and relationships deteriorate. I call this a full-frontal attack by the Vacuum Monster.

Whether it is a dispute between individuals, a workplace conflict or a large-scale conflict affecting an entire nation, when there is an empty space void of information, it will automatically and quickly be filled with something. Unfortunately, 99.9 per cent of the time what fills that information vacuum causes conflict.

The question we need to ask ourselves is: Why is it that the vacuum is almost always filled with information that leads to destructive outcomes? Why is it that commentators are lamenting the demise of public dialogue in nations around the world? Why is it that political and value-based issues are becoming more extreme and more entrenched than at any other time in our history? Why is it that what, in the past, were considered valuable and informative public debates are now seen as us against them trench warfare? Why have issues like Brexit, Aadhaar, immigration and economic reform become so divisive?

The Science behind the Vacuum Monster

Looking at this issue from a behavioural theory perspective, we can see that the human brain is hard-wired to assume the worst. Consider the work of scientists like Jane Goodall, Andrew O’Keeffe, Antonio Damasio and Richard Tedlow. Their writings help us understand why when someone cuts you off in a car you automatically think of him as an inconsiderate driver. You rarely assume he had a good reason to cut you off. Maybe he was on the way to the hospital to welcome his new baby into the world. Their writings provide insights into why we automatically assume the worst. For example, when no explanation is given or reported describing why an unpopular political decision was made, citizens often assume nefarious reasons. They believe it was about poor decision-making, bad judgement or corruption.

There are several reasons for this. From an evolutionary perspective, those early humans who heard a noise in the bush and thought, “I bet that is a cute little bunny” got eaten by the sabre-toothed tiger. Those who assumed the worst, and ran away to hide, lived to propagate our species. All kidding aside, it is an evolutionary fact that an important part of our survival instinct is to assume the worst. It enables us to avoid situations that might cause us harm.

Assuming the worst does not only apply to our physical surroundings, it also spills over to the assumption of intent. Attribution Theory, developed in the 1950s by Fritz Heider, explains that as humans we are predisposed to attribute intent behind other’s actions. This helps us to make sense of our world. Add this to our instinct to assume the worst, and it explains why when someone does something that did or could negatively affect us, we automatically assume that they did that because they are a bad person. Remember the driver that cut us off in the car? Our initial assumption is not that he didn’t see us, but rather that he did that on purpose because he is a rude and inconsiderate person. I once heard Oprah Winfreyii say that whenever she gets a rude taxi driver, rather than not giving the driver a tip, she doubles the tip hoping that will put them in a better mood for the next passenger. I think we can safely agree that Oprah is an exception to the rule.

Another common psychological theory that helps to explain why the Vacuum Monster exists is self-serving bias. Related to Attribution Theory and our human instincts, self-serving bias is the reason that we see ourselves in the best light possible and attribute the bad stuff to others. It is why my son tells me how brilliant he is when he gets an A on a test and how bad the teacher is when he gets a C. It also explains why in a conflict situation, each side attributes to themselves the moral high ground and sees the other side as the proverbial snake in the grass. Social psychologists call this the Illusion of Moral Superiority (Tappin & MacKay, 2017). “When opposing sides are convinced of their own righteousness,” note Tappin and MacKay, “escalation of violence is more probable.”

Most societies have a fable like the story of the ugly duckling where the baby bird imprints on the wrong mother when it hatches. The other barnyard animals see it as an ugly duckling rather than a cygnet (or a baby swan). In humans, this is called the “speed of classification”. We are imprinted immediately when we meet someone or something new.

We often call these first impressions, and first impressions are, as we know, very hard to change. Classifying or imprinting again is related to our survival mechanism. As humans we classify things in binary fashion: good/bad, dangerous/safe, like/dislike, us/them. This helps us make sense of the world, and our brains do this very quickly. Like the chick that imprints on the first thing it sees upon hatching, human instinct is to make an immediate first impression. We then use that impression to attribute cause and effect. This helps us to make sense of our surroundings and our place in the world. Remember, Maslow’s theory of self-actualization and hierarchy of needs tells us that understanding our place in the world is a universal human ambition.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out, interpret, judge and remember information that supports our pre-existing views and ideas. This is also referred to as my-side bias. The National Academy of Science recently published a global study of 376 million Facebook users. The study highlights the important role that confirmation bias and selective exposure plays in reinforcing our world views. The study suggests that this also contributes to our emotional response to polarizing societal issues. Arun Maira, part of India’s Founding Fuel,iii describes how this phenomenon is exaggerated by social media. “Social media… force[s] people into self-reinforcing echo chambers, in which people follow who they like and lob hate-bombs across the walls of their echo chambers at people they do not like. It is not designed for thoughtful deliberations, in which people are willing to listen to other points of view. It too quickly and sharply divides people into groups who are for something and those who are against it; into communities of ‘people like us’ and ‘people not like us’.”

Knowing that humans immediately classify things in binary fashion also helps us to understand the human aversion to loss. If our brains were wired to seek pleasure above avoiding pain, our species would not have survived. This is why the avoidance of loss is a far greater motivator for people than the opportunity to gain. It also explains why, when something happens that we do not understand, we immediately assume it is going to result in some sort of loss for us. And avoiding loss is our number one priority. Let’s go back to the early man who heard the noise in the bush. The one who immediately reacted to avoid loss survived.

Emotion before reason also falls under this same rationale and contributes to our fight or flight instinct. Emotion helps us to attach meaning to the world around us. People make sense of events based on how it made them feel. Human beings do not suspend judgement until we have learned all the facts. Instead, we jump to conclusions based on our emotional response to a situation. We anticipate the reason behind actions and events. We assume intent of those involved. This is why, when we hear the name of a politician, we will often either have a feeling of pride or a visceral feeling of dislike, based on which political side that politician is on. Our feeling will depend on whether he/she is in the “like us” or “not like us” category. This is also why we tend to emotionally fall back on black and white arguments. Especially when we are speaking about issues like the economy, security, human rights, resource development, immigration and privacy. Even though we may understand logically that there is a large grey area, we tend to stick to the black and white zones.

The Vacuum Monster feeds on Attribution Theory, self-serving bias, the speed of classification, the fear of loss and our tendency to use emotion before reason. When there is a void of information, each of these behavioural traits contribute to the empty space being filled with negative ideas and assumptions. The Vacuum Monster tips the conflict scale towards destructive outcomes and away from constructive ones. I argue that the power of facilitation can help us to slay the Vacuum Monster—and our weapon of choice in this epic battle is LIGHT.

The Power of Facilitation as Vacuum Monster Slayer

By bringing the information into the light, facilitation has the power to make the invisible visible.

Light energy has amazing qualities. It is a great disinfectant and at the same time an amazing growth agent. Facilitation can help individuals and groups to bring the information that filled the vacuum out into the light. Facilitators can help people to share with each other their individual interpretation of history. Facilitators can help them to explore their assumed intent as to why people acted the way they did. They can then examine what it meant to them and the emotional reaction they felt/feel. Sharing assumptions is often all it takes to create a shared understanding. It can help to remove the “misses”— misinformation, misinterpretation and misconceptions—and to identify a way forward.

Take, for example, a child’s dot-to-dot exercise. When there are dots on a page with clues and numbers to guide us, everyone creates the same image. However, if you take away the numbers, clues and context, people may connect the dots differently, drawing their own image or conclusions. Rorschach created a whole genre of psychological tests using this same concept. Add to this the confirmation bias discussed above, and we have much for the Vacuum Monster to feed on. Facilitation has the power to open and hold the space for groups and individuals to share their mental images. It also allows them to share their assumptions, interpretations and emotions around an issue.

One of the most powerful tools that facilitators have to bring information into the light are what I call original questions. Original questions go back to base principles and answer the question “why”. I have three sons and when they were young their favourite word was “why”. When we told them to eat their peas, they asked “why”. When we told them it was time to go to bed, they asked “why”. When their great-grandmother passed away, they asked “why”. Of course, for those of you with children you know that every “why” question is followed by an average of at least three other “why” questions. This is the way children typically make sense of their world. Original questions are the base questions that help us make sense of a situation or issue.

Let’s take an example of a leader who is frustrated about the continuous conflicts happening between departments. If the leader deals with each conflict on the surface (what happened to cause this conflict) immediate fires might be extinguished. But the embers remain and have the potential to reignite or, worse, cause a catastrophic fire that could spread across the entire organization. What the leader needs to do is continue to ask “why” questions until he or she finally gets to the original question— the question that tells her why the conflicts are happening. It takes this child-like curiosity of asking “why” for the leader to understand not only what is going on, but why it is happening. Only then can she begin to help the departments to work together towards constructive outcomes, rather than destructive ones.

Examples from the Field

I have been asked to help many workplaces and teams who are in situations of extreme conflict to find constructive solutions that will allow the organisation to successfully meet its mission and goals. What I find is that they almost always have in common two conditions/problems. The first I call the Ostrich Syndrome and the second the Broken Camel.

The Ostrich Syndrome is simple: the leadership has had its proverbial head-in-the-sand for a long time. This means they have either ignored or enabled the conflict to remain unresolved for so long that the situation has hit a critical level. They have allowed the conflict to negatively impact the organisation’s bottom line and its ability to deliver on mission critical objectives. Less than 18 per cent of managers are reported as being effective at dealing with conflict (Psychometrics Canada Ltd, 2015), which may be one reason for this. Too many leaders and managers ignore conflicts in hopes that they will go away on their own. They hope that people will forget about it and move on. Unfortunately, that rarely happens.

The second condition I refer to as the Broken Camel. We all know the saying, “The straw that broke the camel’s back.” In most organizations I deal with, the leadership has not only ignored one conflict, but they have ignored or swept under the rug many small conflicts. Over time, the many small conflicts have built up to create a massive problem. In my experience, there is rarely one thing that caused the conflict. It is usually hundreds of unresolved small things that have slowly eroded the team’s ability to communicate, trust, solve problems, work together and think together effectively.

In these types of situations, I have adapted the Institute of Cultural Affairs’ (ICA) Journey Wall method (see appendix A). We use it to identify significant events or situations that have occurred and have impacted the organization, the team or individual staff members. The staff writes each event on a card and sticks the cards on the Journey Wall. The Wall is at least ten metres long, with a date ruler across the top. Today’s date is on the far-right hand side and the ruler counts back in time from there. Depending on the organisational history and length of time the staff has been with the organization, the ruler may count back a few months, a year, ten years or longer. In a staff group of 15–20 people, we would typically have 150–200 cards on the wall by the end of a two-hour silent reflection time block. This may sound like a long time, but remember we are dealing with a conflict situation that has evolved or grown over many years.

In the second step of the process, the facilitator engages the team in a dialogue about each card. They discuss what happened, people’s different interpretations of what happened. They examine how it made them feel, what assumptions were made and the impact all of that had on themselves and the organization. This can be a very intense and difficult conversation, and requires a facilitator skilled in dealing with highly emotional, often divisive dialogues. However, the benefits of this approach are immeasurable! As participants see the value of ‘digging up the old dirt’, they start to say things like, “I had no idea that is what you thought,” “I didn’t realize that was why x happened,” “I wish you had told me that earlier,” and “But I thought you said that because…”

The exercise can take days to complete in highly entrenched conflict situations. But the increase in self-awareness, team awareness, understanding, trust and empathy is worth the time and effort by everyone involved. Shining a light on each of the issues/events allows the team to start to unpack and examine each little straw on the camel. They begin to lighten the load, making it much more manageable. As the facilitator moves participants down the Journey Wall, there is also a great deal of problem solving that takes place. Lists of action items are developed to reverse past mistakes, correct gaps in policies and procedures, document new agreements and commitments, etc.

I have used this process with corporate groups, healthcare teams, educators and community groups and I am ALWAYS amazed at the results. One participant told me after a very long and emotional three days, “This was the most difficult and rewarding three days of my life.” I recently met a manager that was part of a team I worked with more than five years ago and she told me that her staff still refer to the Journey Wall we did and remind each other about the lessons they learned through that process. Her comment was, “Before you helped us move into the light, we were failing on all organisational measures, but since those sessions we have met every organisational target and we have a much happier workplace!”

The most important outcome of any facilitated process designed for groups in conflict is to teach and embed positive communication skills and norms. It enhances the abilities of the group to think together. This is crucial so that the team can deal with future conflicts constructively. It leads to positive outcomes and better relationships. I always preface these types of engagements with the concept that team members do not have to be best friends to be able to work together effectively. They do, however, have to be good colleagues who trust each other’s professionalism. And if I do my job well, I will work myself out of a job!

This is what skilled facilitation of a processes, such as the Journey Wall, can create or recreate. When the Vacuum Monster is attacking a team, shine light on the information void and see what you can uncover. You and the team will be amazed at what you find.

The Power of Facilitation in Solving Large Scale Societal Conflicts

The same principles hold true for community conflicts. The power of facilitation can help the parties better understand each other’s point of view. It helps people to appreciate other perspectives and, often for the first time, to begin to truly listen to each other. It is not necessary to agree on every point, but it is critical that the parties understand each other’s beliefs and points of view. Shining a light on the information vacuum will disinfect it of negative assumptions and misinterpretations—at the group level, the organisational level, the community level and the national level.

Take for example, a community in conflict with a neighbouring manufacturing plant. Facilitation has the power to create the time and space to hold authentic conversations and to remove assumptions of intent.

Once the parties start to communicate and better understand each other, they will stop seeing the situation as us against them. They will then be able to work together to resolve the issues plaguing them both. It changes the situation from me against you to us against the problem. They will be able to challenge their own assumptions about the intent of the other parties and open their minds to the possibility of working together towards a constructive outcome. When that happens, the facilitator can step back and allow the parties to think together and work towards a common goal. That is the power of facilitation.

There are many examples where the power of facilitation has been used on a large scale to successfully slay the Vacuum Monster, even when it is attacking whole countries. The five examples outlined below, demonstrate how the power of facilitation can help societies in conflict achieve constructive outcomes.

There are four elements that each of these inspiring international examples have in common:

- Each created the time and space to shine light in the vacuum. They allowed the participants to poke around, explore and discuss what they saw. They allowed people to examine the issues, the evidence and remove assumptions and mis-information.

- Each was built on the belief of the innate wisdom of the group. They believed that the wisest choices are made when all voices are heard. They knew that no problem is unsolvable and made no conversation off-limits.

- Each reverted to the base principles and asked the original question— WHY. They allowed participants to explore their ideas and better understand others’ ideas rather than just jumping into debating the resolution or answer;

- Each framed the exercise as a dialogue designed to resolve an issue. They did not frame the conversation around choices or finding a solution to a predefined problem.

Without difficulties, life would be like a stream without rocks and curves—about as interesting as concrete. Without problems, there can be no personal growth, no group achievement, no progress for humanity. But what matters about problems is what one does with them.

The Te of Piglet by Benjamin Hoff

These examples remind us that there is no problem so big that a group of people cannot solve it. They also demonstrate the importance of time, space and process, and the willingness to consider issues with a child-like curiosity and genuine inquisitiveness. The power of facilitation is based on the belief that people have the innate ability to understand, think through and resolve issues. Facilitation can help solve large-scale and deeply entrenched problems. It harnesses basic human ingenuity and provides an avenue for it to thrive, even in times of deep conflict. Facilitation enables us to think together.

Conclusion

This chapter focused on the power of facilitation as an enabler of positive public dialogues and critical conversations and as a tool to use when piloting conflicting parties to a sustainable resolution. This is not a new concept—we are not reinventing the wheel here. As mentioned earlier in this chapter, and in the other chapters in this book, discussing issues through various forms of open conversation has been how our species has evolved. Dialogue and deliberation may be new wording, but the concept is ancient—when you have a problem, talk it out and don’t stop talking until the problem is resolved to everyone’s satisfaction. But somewhere along the way, in our collective race to be better, faster and stronger, we have forgotten this most basic of concepts.

Facilitation is a process that helps us to remember how to talk it out or, as Peter Senge says, think together. Facilitators spend years, lifetimes even, perfecting the art of helping individuals, groups, teams, communities and societies recall and employ that most basic of skills. The power of facilitation is that it provides the time, the space and the processes to guide people through the reactivation process of remembering how to ask original questions. It helps us to hold genuine dialogues, even about issues about which we have very deep and conflicting feelings or beliefs.

The Vacuum Monster is indiscriminate; it will attack individuals, groups, teams and nations.

Facilitation has the power to help us to embrace the notion of constructive conflict— moving from “beat and defeat” to “together we can”. So, the next time you are faced with a conflict, grab your nearest facilitator, or take on the role yourself, and slay that vacuum monster. Help to shine light on the information, allow people to talk it out and foster the can-do attitude that has helped mankind to evolve and thrive through millennia.

References

i. What’s a Wicked Problem? | Wicked Problem. (2010). Stony Brook University. https://www.stonybrook.edu/commcms/wicked-problem/about/What-is-a-wicked-problem

ii. Wikipedia contributors. (2021, April 30). Oprah Winfrey. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oprah_Winfrey

iii. Founding Fuel is an entrepreneurial think-tank based in India, https://foundingfuel.com/

iv. REACH Singapore. (2020). Our Singapore Conversation. Base. https://www.reach.gov.sg/read/our-sg-conversation

v. The Guardian, International Edition. January 22, 2019. ‘Transparency and fairness: Irish readers on why the Citizens’ Assembly worked’.

vi. Jefferson Centre’s report on Rural Climate Dialogues, https://jefferson-center.org/rural-climate-dialogues/

vii. CP Yen Foundation Report – Imagine Taiwan, https://cp-yen.ning.com/

viii. Tom Atlee, The Co-Intelligence Institute, https://co-intelligence.org/S-Canadaadvrsariesdream.html

You must be logged in to post a comment.