Teamwork is the ability to work together toward a common vision. The ability to direct individual accomplishments toward organisational objectives. It is the fuel that allows common people to attain uncommon results.

Andrew Carnegie

Group facilitation generates conditions similar to the behaviours, social context and practices of high-performance teams. What we mean is that fruitful collaboration can occur even in new groups or low performing groups. Through these experiences, the members of the group can see the window of possibility of what they can achieve and what can happen if they transform into a team. In regular conditions it takes a long time to develop these behaviours. Or it requires a significant change in the behaviour of the leader or time to implement.

By reading this chapter, team members, leaders and facilitators in general will be able to discover how the power of facilitation impacts the development of a group, how it accelerates its performance and establishes a path for the groups’ evolution into a team.

Some people might say that you can’t expect much of a new group, in terms of results or efficiency. I’d say that assessment is generally correct, unless the group engages in effective group process facilitation practices led by an experienced facilitator.

Humans as Social Beings

In the last fifty years, plenty of media sources, business books and social media have focused on the individual as the source of creation, development and progress. As if one person in isolation can bring about phenomenal change. But, if we look closer, it is our capability of coming together and becoming a cohesive social group that has enabled human progress in all areas. We are indeed social animals.i

Anthropologists have concluded that one of the two main reasons Homo sapiens were able to surpass other species was the capability to act together. In the early dawn of humanity, it was cooperation that allowed one group to establish dominance above others.

It is the long history of humankind (and animal kind, too) that those who learned to collaborate and improvise most effectively have prevailed.

Charles Darwin

Even when compared with other social animals, humans are especially cooperative,ii sometimes even referred to as the ultra-social animal.iii

From religion to education, from economy to technology, it is this capability to organise ourselves, define roles, establish goals and work in the company of others that has made the difference. It has enabled human-kind to be the predominant species on planet Earth. We go as far as needing cooperation to reproduce and take care of our offspring. We can say cooperation is ingrained in our DNA. “We eat better when we work together,” the saying goes, and there’s a lot of truth in it.

As a society, we enshrine specific individuals as heroes in our collective road of advancement. Encyclopaedias are full of examples. Yet, it is the incredible capability of human groups to come together, that truly advanced the creation of civilizations across the ages. Chapter 8 explores further our collaborative nature.

Nevertheless, results vary tremendously from group to group. Even within the same organization, groups working under similar if not identical conditions can have significant variation in performance.

Nowadays, it is common to hear that when people come together in a meeting, they often end up frustrated. Participants get tired and leave in a worse emotional and relational state then before they started. Attendees need a meeting to follow-up on and debrief the ineffectual meeting. It so happens that even a word has been coined for this phenomenon: “meetingitis”. The Urban Dictionaryiv defines it as when an organization or individual has so many meetings that completing actual work is near to impossible.

Why did all this happen? Aren’t we social by nature? Aren’t we most effective when we work together? What’s the cause of all this frustration?

I believe that the complexity of today’s society and the incomplete tools we are given in our traditional education system deter collaboration. Our attachment to old habits and work structures limits the capability of most groups to work together effectively.

Here is where the power of facilitation can make a difference. Facilitation takes into account the necessary variables to make group collaboration a success. From preparation to method selection, energy use to conflict resolution, facilitation has the power to oversee the socio-emotional aspects of the group members. It can also manage the information flux needed to solve an issue or complete a decision-making process.

It is the facilitator’s job to aid the team to arrive at the best result possible with the resources at hand and in the available time. This includes opening the communication channels between the participants, allowing the flow of ideas, better acceptance of action plans and increasing consensus. This, in turn, provides higher quality results, while maintaining or even improving relationships.v

From Groups to Teams, from the Gate to the Goalpost

We have established that being in a group comes naturally to us as human beings. Reviewing some of the literature about social groups it is clear that human groups are not necessarily equal in their performance, development or output.vi Some groups have developed certain behaviours that have made them much more effective and efficient. All of this while maintaining social cohesiveness. Several authors identify these groups as an evolved state with a new name: a team.

I like to think of these differences in behaviours, values and attitudes of the members of groups and teams as part of a continuum in the evolutionary process of a group. On one side of the spectrum you have a group. A group has a very basic reason for the individuals to be together and gather or it may be that its members have just started to interact with one another. As the relations between the members and the agreed-upon conduct of the group improves, the transformation starts, and the group moves to the right of the continuum, increasing its achievements and results.

From Groups to Teams

For example, let’s take a group of airline passengers ready to board at the airport’s gate. They all have the same goal: arrive at their destination. The performance of the group is based on an accumulation of individual goals, similar to “I want to arrive at a specific city.” Besides that, the relationships between its members, their goal of “how to get there” could be quite different.

Let’s compare this with a Football World Cup champion squad. A team considered by many to be the epitome of a high-performance team. Its 23 members have an overall goal of winning the tournament. Their individual goals may be quite different—forwards focus on scoring goals, defenders on stopping the attackers and the goalie to maintain its net undefeated. It is their relationships, training and communications that allow them to become victorious.

As Kimberly Bain has often told me, many authors/theorists equate the natural evolution of groups into teams as a linear process, which only requires time and effort to be accomplished. However, not all groups that spend a considerable amount of time together actually become what is generally considered an effective team.

At any given time, a group might be moving to the right or left of this continuum. This will change depending on how they express their values of collaboration, respect and balance between an individual and the group. In a team this translates into specific behaviours: active listening, planning, focused discussions, follow-through, conflict management, decision-making and consensus.

Tuckman’s Model

Back in 1965, Bruce W. Tuckman produced a relatively short research article.vii This article, just 15 pages long, had a tremendous impact on how we see the development of groups. The Tuckman Model is also better known as the “Forming-Storming-Norming-Performing Model”. Over the years, it has provided the basis for evaluating the development/ maturity of a team for several methodologies. It has also served as a basis for many leadership development programmes.viii

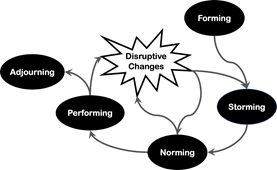

In a quick summary, the different stages establish a critical path groups typically go through. This development process is not always linear. Tuckman suggests that sometimes groups can go from Stage 1 to Stage 3 without having to go through Stage 2.

The stages identified by Tuckman’s Model are:ix

Stage 1 – Forming: At this stage, members are not fully familiar with the situation. The leader or person in charge has noticeable power and makes use of it. At this stage, members of the group meet together and directed by the leader, they identify the team’s objectives and their own goals and tasks.

I think we can all relate to the words of Gene Kranz, former NASA Flight Director, at the start of his career when he wrote, “I found it difficult to believe that the people in my building were the core of the team that would put an American in space. For the first time in my life I felt lost, unqualified, but no one sensed my confusion. Then I thought, maybe they feel just like me.” (Kranz, 2000). Many members of a team can feel like this at the beginning of a journey with a new team.

Stage 2 – Storming: Conflicts arise due to different work styles, unclear tasks/roles and personal backgrounds. Here is where clashes and conflicts happen. For example, a team member challenges the authority of the leader, or the group members experiencing stress due to lack of roles and clear authority lines. Usually, if the problems in this phase are not resolved, the team (or its performance) dies with it. The arguments that arise here can make the unit stronger if addressed properly. Groups may continue at this stage for a very long time when issues are not resolved.

Stage 3 – Norming: Conflict management and socialization help resolve differences and allow people to work together. This stage often overlaps with storming because new tasks can affect behaviour. Groups that emerged from the Storming phase would have developed intimacy and common responsibility towards its goals. Norms in a group change all the time, new processes as well as updated guidelines, policies and responsibilities need to be established. This commitment to the common goals allows the team to face any issues, even the most difficult ones and agree on new courses of actions.

“There is no feeling in the world to compare with the feeling you get when you know you blew it, and you have to explain in excruciating detail during simulation debriefing why you acted as you did. There are no excuses,” explained Gene Kranz, about their internal review processes when learnings are internalized, new processes thought of and the new norms were established in order to get the first manned crew to the moon.

Stage 4 – Performing: This is where the team attains success through hard work and deep knowledge. Work results are visible, as the relationships and rules of work have been internalized by the members of the group. The leader can concentrate on team development and improving performance. Tuckman proposes that the highest-performing teams are the ones that self-organize, without needing a leader to organize the tasks, responsibilities and rules for them. The leaders’ intrusion may use energy and resources inefficiently. Traditionally, leaders are further away from the issues than the members of the team.

Again, Gene Kranz summarizes this in his experience at NASA, “There are times when an organization orchestrates events so perfectly that the members perform in perfect harmony. It is part of team chemistry, where communication becomes virtually intuitive, with teams marching to a cadence, the tempo increasing hourly and the members never missing a beat.”x Then he adds, “…you simply had to have trust in your crew, your team and in yourself. Through trust you reach a place where you can exploit opportunities, respond to failures, and make every second count.”

If everyone is moving forward together, then success takes care of itself.

Henry Ford

Stage 5 – Adjourning: Teams made for projects dissolve after achieving their goals. This stage was created by Tuckman and Jensen almost a decade after the original model was published.xi Some authors identify that this stage can also be an “adjusting” stage. Smith states that when critical changes happen to the group, it impacts it in a fundamental way. Some examples are new leadership, new goals or significant process changes.xii

At the end of this chapter, I share how a facilitator or team leader can manage these stages and expedite movement towards the performing stage.

It is important to understand, however, that some teams may not move beyond a certain stage. Groups can get stuck, for example, in the Storming stage, in which the team still is in the process of managing internal conflict and dissent. This could provoke an environment of low motivation within the team. A lack of results can increase the conflict as well. All of this may result in the need to change the team members or the team leader.

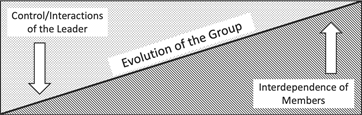

One of Tuckman’s novel ideas was that when the team arrives at the performing stage, the role and interactions by the leader are reduced. This happens as team members increase their interdependence. Interdependence allows the members of the group to solve the issues between them instead of having the leader step in every time. This allows a freer flow of information, quicker decision-making and, in the end, better results.

Leader Interactions and Members’ Interdependence

We can see striking similarities in the characteristics Tuckmanxiii presents with some of the core components of what is generally considered good process facilitation.

The Evolution of the Group

While the model has continually stood the test of time, Smith proposes that instead of just an upward-evolving process, the model needs to be viewed as a series of cycles. The group might encounter situations, which increases the stress in the group (new members, new goals, new leaders, etc.), thus impacting its performance. He states that a new Storming stage happens in the life cycle of the group that needs to be sorted out through a new Norming stage.

We can interpret this evolution of the group in a graphical way as a continuous evolutionary cycle.

For example, if the group is performing at a high level for a considerable amount of time and a change of leadership happens (that reason itself could be a source of disruption as well). If the team is small, let’s say a team leader with two or three reporting staff, then most certainly a Forming stage can be identified, new relationships need to be established and uncertainty needs to be clarified. Possibly different rules will be implemented by the new leader and new processes will be agreed upon.

If the team was high performing, the staff members could already operate with a great degree of liberty. The group could thus go to Norming directly, as one of the scenarios that Tuckman envisioned. This will depend greatly on the personality and leadership style of the incoming manager within the social context of the group.

However, if the performing team has a considerable number of members, it is a whole different scenario. Normally, large performing groups have defined and structured internal processes. They have well-established relationships as well. If the new leader is selected from within the team, it is possible that the change will be less disruptive, and the group will only go through a new Norming phase unless, an internal struggle for the leadership position fractures the group into a Storming phase. Any of these scenarios can benefit from facilitation processes. Facilitated agreements can smooth out the transitions. That is one of the ways that the power of facilitation manifests in creating better teams.

The facilitator ensures the goal is shared, the rules are obeyed, the structure is followed, the power is shared, and the results are committed to.

As we have shared, all these changes take time to occur in the normal evolutionary process of a group. Facilitation can disrupt this cycle altogether and, accelerate it in a significant manner.

It doesn’t matter which stage the group is in. It may be that the group is an ad-hoc one, meaning that it has been brought together for one occasion (Forming stage). The group may have some internal issues that haven’t yet been clarified (Storming stage). It might even be producing very good results (Performing stage).

The power of facilitation provides a springboard and acts as a catalyst to transform groups into teams in a short period of time. A facilitator will take this into account when designing the process. The facilitator will ensure the processes are at the level needed, so the group can perform as a unit during the engagement. The facilitator ensures the goal is shared, the rules are obeyed, the structure is followed, the power is shared, and the results are committed to.

The facilitator aims to move the group into the performing stage as soon as possible, making an efficient use of the limited time available. The facilitation intervention may not transform the behaviours permanently though. It will transform them just enough to get the work done if it was appropriately designed and effectively executed.

In many ways, good facilitation practices also coincide with Google’s findings in their research on high-performing teams. In 2015, Rozovskyxiv shared that Google found that there are five key dynamics that set successful teams apart from other teams:

- Psychological safety

- Dependability

- Structure and clarity

- Meaning of work

- Impact of work

A good facilitated process supports all these elements, thus ensuring optimal conditions for the group to perform.

Teams Good – Meetings Bad

The strength of the team is each individual member. The strength of each member is the team.

Phil Jackson

In order to do their work, teams need to gather. Team gatherings are generally called meetings (although in Keith’s Taxonomy of Meetingxv you can find more than two dozen other words for it). In the last decade, the backlash against meetings in social and business media has grown exponentially. A quick online search shows that meetings have a very bad reputation.

It is not uncommon to hear participants complain about having to attend “yet another meeting”, not having any time to actually get some work done. In several surveys, participants share that in quite a few occasions they are not clear on why they meet. Regular meetings usually fail in this regard, according to several studies.xvi

When an organization hires a professional facilitator, it aims not only to have a “great experience” or a “marvellous corporate retreat”, but to get specific tangible results out of the time and effort invested by the participants.

Facilitated meetings at their core are “deliverable-specific”. It means there is a very well-defined outcome expected from the meeting. The facilitator may plan one or several group sessions in which he will guide the process, allowing the participants to arrive to the deliverable they consider is the best option to go forward with. So, there is quite some work to be done prior to the participants coming together.

The power of facilitation can transform a group of strangers, or sometimes even individuals with a certain degree of mutual dislike, into a team. It can take a diverse group of participants and turn them into a cohesive unit focused on specific and carefully designed tasks.

Effective meetings don’t happen by accident; they happen by design.

Andrew Carnegie

I believe this is a critical differentiator of a professional group process facilitator from other experts. It understands that human groups can be quite complex by their very nature and proper preparation and session design as stated in the International Association of Facilitators Core Competencies is fundamental for a successful facilitated meeting.

Transforming a group into an effective team during a session does not happen by chance; it happens through careful design. Below, you can see some similarities between behaviours of high performing teams and successfully facilitated meetings.

The Facilitator as a Catalyst for the Group/Team

The facilitator aids the group without being a part of it. He focuses on the process the group is going through, so the participants can focus on the content. The facilitator aims to remain “neutral”, meaning that she does not take sides on the discussion and does not manipulate it to arrive at a certain conclusion. However, the facilitator does have the means to “push/pull” the group to arrive at where group members have agreed and to fulfill the objectives of the session.

The facilitator is the process leader, not the team leader. This allows the participant to trust in the process, by trusting the abilities of the facilitator to guide their deliberations in a way that achieves their objectives.

This balance between performance (task focus) and participation (group engagement/ satisfaction) is the critical aspect that provides much of the power to the facilitator to help transform the group into a team. Being an external participant in the content, the facilitator can protect the meeting process, or at least control some of the complications that can be seen in the Storming and Norming stages of group development.

Great things in business are never done by one person. They’re done by a team of people.

Steve Jobs

If we think about it, the facilitator has to help the team go through the “Forming-Storming-Norming-Performing” process quickly and efficiently to achieve the desired results in the desired time frame. To understand how a facilitator does this, we can equate the facilitator as a catalyst.

A catalyst accelerates what could take much more time in a regular environment. As a catalyst, the facilitator changes the way participants interact with each other and with their leader (or leaders). It even impacts their normal day-to-day rules and behaviours. Facilitation increases the speed of interactions, idea generation and collaboration.

Case study: The Consulting Company

Several years ago, a multinational consulting company hired me to support their annual corporate congress. They had been doing the event every year for the last five years but had never hired a facilitator. The company had over forty offices. A core team from seven offices was responsible for the congress, making all major decisions, including setting the agenda.

Past agendas basically assigned time slots to discussions in an open forum and included issues that related to all offices or case studies of services delivered the previous year. However, previous years’ participants complained that engagement was low, and nothing was achieved at the congress. Participation in the congress was declining, with less than 15 offices participating in the previous year. The goal of this year’s organizing committee was to turn the congress around. They told me they wanted to increase participation and engagement.

From the beginning, during the planning interviews with the core team offices, it was recognized that this needed to be a radically different event. We began by agreeing to and documenting their aims, both relationally and in terms of deliverables. It was agreed that the main goals would be improving relationships and information exchange. They wanted to transform the perception of the participating offices.

By utilizing planned facilitated processes during the congress, participants changed how they saw and supported each other. Several months after, some of the participants mentioned it was a pivotal point. Now they could actually reach out to the other offices as they knew what the other countries could offer them not only in terms of know-how and expertise, but they also felt confident enough to exchange ideas and possibilities.

They went from the Storming to Norming stage during the congress. After the rules and processes were agreed upon and were used, they moved to the Performing stage. They improved the knowledge flow between the different offices significantly. They did this by opening direct communication channels and by acting like a high performing team. The company continued to hire a facilitator every year to help plan and facilitate their congress. That’s the power of facilitation!

Case Study: The Hospital Directors Cabinet

Another example that comes to mind is when I was requested to work with the team of Directors of a hospital with over 300 beds in the Caribbean. They realized that they needed a facilitator to help them define their Mission and Vision Statement as a team.

The team included the hospital director and the senior management team. The members were quite varied. There were doctors and nurses, pharmacists and engineers, accountants and administrators—each one with his or her unique point of view of how the hospital needed to be run.

During a half-day engagement, the team aimed to reflect and define their reason of existence and their vision for the hospital. As the discussions progressed, they realized some of their processes for exchanging information were not aligned with their Mission. They then decided to invest the remaining time of the session to redesign their own processes to help this exchange.

What happened was that they invested time in clarifying the best procedures that could help them think better together. For them this was mind-opening, as they realized their boring mid-week meetings could transform into a forum with the capacity to move ideas and initiatives forward.

I had a chance to observe the team meetings before and after the engagement. Their monthly review changed tremendously. What was once a dreaded task, became an energetic review of the programmes and initiatives happening across the whole organization. In individual conversations, they shared that they had realized that their own internal processes as a team had to be updated continuously to be effective. This is also the power of facilitation.

The Power of Facilitation on Group Trust and Team Building

Common team-building engagements tend to focus most of the time on the “soft” side of skills development. It usually aims to “increase communication” among its members. Goals for this type of activities tend to use descriptors such as: create connections, generate trust and improve relations between team members. We can relate them to Tuckman’s Model in many of its stages.xvii

In contrast, in a facilitated environment, the members of the group do not necessarily have to trust each other prior to the meeting (although it helps plenty for a good process). It is the facilitator who needs the participants to trust him or her, so they can trust the process that has been designed. Being a foreign entity to the group, sometimes it is easier for the participant to trust the facilitator than the “guy from the other department” because of past history and its relations. So, in a way, the facilitator becomes a repository of the trust capacity of the group. And as we’ve read before, trust (Google calls it dependability) is a critical element for group performance.

It is during this process that conversations, when conducted in an open and receptive manner, can become the seed for a longer term improvement of the relationship. This in itself has the potential to transform the group. As Tuckman established, it is the quality of the relationships between the members of the group that makes its communication and decision-making effective. The more and better the trusting relationships, the higher the performance of the group.

It is not uncommon after a facilitated session to hear expressions from the participants such as, “I would have never thought that Mr. Z could be so interesting to work with.” Or “Ms. Y definitely brought some new ideas to the table.” This can spark a whole series of initiatives after the facilitated session is over.

Engaging the Power of Facilitation for Team Development

When preparing for a facilitated session, the facilitator and the team leader/ manager/ sponsor need to understand where the group is in terms of its development stages (Forming-Storming-Norming-Performing-Adjourning). This can be the key to a successful design and can have a lasting impact on the development of the team.

Let’s take the case of a new group with representatives from different stakeholder sub-groups. Here the facilitator needs to invest enough time in the Forming-Storming phases. This is to ensure there is enough trust to really get deep in the conversation to achieve the required outcomes.

On the other hand, if the group is already in the Performing stage, investing time to go through a Forming phase during the session could even be counterproductive. I’ve heard a term used in such cases as “over-facilitating”, when a facilitator interrupts the flow and energy of the group.

Once you understand where the group is you can design your session and timings in accordance to the group’s maturity and define how much effort is needed to go through each of the stages to achieve performance.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have seen how facilitation has the power to transform the relations between group members. The facilitator can accelerate the development of a group by creating the appropriate conditions and designing processes needed to optimise group performance.

Properly utilized, facilitation has the power to expand the capabilities of the group. During a facilitated session, group members practise behaviours that help the group evolve from the Storming or Norming stage into Performing. Behaviours such as active listening, respecting everyone’s points of view or adhering to a set of rules for meetings and decision-making which are all critical for a group to improve performance.

In the end, facilitation can bring about one of the most powerful effects in human relationships: build trust among the members of the group. As Warren Bennis said: “Trust is the lubrication that makes it possible for organizations to work.”

Recommendations for Facilitators

(A Mini-Appendix)

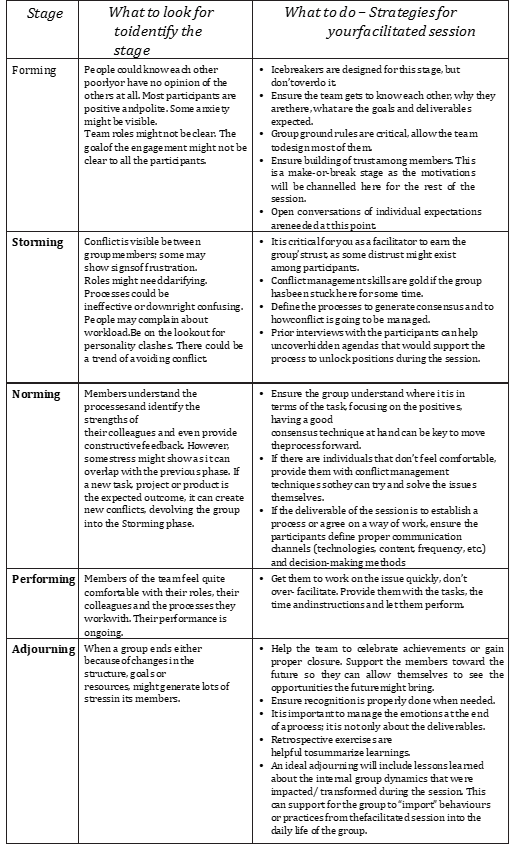

Notes and recommendations for facilitators on what to look for and do when designing a facilitated session.

References

i. Aronson E. (1980). The Social Animal. Palgrave Macmillan.

ii. Wilson E. (2012). The Social Conquest of Earth. Norton.

iii. Tomasello M. (2014) The Ultra-Social Animal. European Journal of Social Psychology, Apr 44 (3): 187–194.

iv. Urban Dictionary (n.d.) Meetingitis. Retrieved 04-22-2019 from https://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=meetingitis

v. Langeberg, E. L. (2017, August 20). Google Design Sprint Facilitation – My Top 10 Learnings. Linkedin. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/google-design-sprint-facilitation-my-top-10-emiel-langeberg/

vi. Napier, Rodney W., & Gershenfeld, Matti K. (1973). Groups: Theory and Experience. Houghton Mifflin Co.

vii. Tuckman, Bruce W. (1965) Developmental Sequence in Small Groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63, 384-399.

viii. Smith, M. K. S. (2005). Bruce W. Tuckman – forming, storming norming and performing in groups. Infed.Org: Education, Community-Building and Change. https://infed.org/mobi/bruce-w-tuckman-forming-storming-norming-and-performing-in-groups/

ix. Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing (n.d.) Forming, Storming, Norming, and Performing. Understanding the Stages of Team Formation. Mindtools. https://www.mindtools.com/pages/ article/newLDR_86.htm

x. Kranz, Gene. (2000). Failure is Not an Option. Simon & Schuster.

xi. Tuckman, Bruce W. and Jensen, Mary Ann C. (1977). Stages of Small-Group Development Revisited. Group & Organization Management, 2(4), 419-427. Copyright 1977 by Sage Publications. Reprinted with permission in Group Facilitation: A Research & Applications Journal, Number 10, 2010. ISSN 1534-5653

xii. Smith, M. K. (2005). Bruce W. Tuckman – Forming, storming, norming and performing in groups, the encyclopaedia of informal education. Retrieved: 01-07-2019 from https://infed.org/mobi/bruce-w-tuckman-forming-storming-norming-and-performing-in-groups/.

xiii. Nestor, Rebeca (2013). Bruce Tuckman’s Team Development Model. Leadership Foundation for Higher Education. Retrieved March 28, 2019 from https://lfhe.ac.uk/download.cfm/docid/3C-6230CF-61E8-4C5E-9A0C1C81DCDEDCA3

xiv. Rozovsky, Julia (2015-10-17). Five keys to a successful Google Team. Retrieved in 02-06-2019 from https://rework.withgoogle.com/blog/five-keys-to-a-successful-google-team/

xv. Keith, E. (2019). A Periodic Table of Meetings (with Free Download). Elise Keith. https://blog.lucidmeetings.com/blog/periodic-table-of-meetings

xvi. Charles. (2019, June 16). Klaxoon’s study reveals insights on the future of teamwork in America. Klaxoon Blog. https://klaxoon.com/community-content/klaxoons-study-reveals-insights-on-the-future-of-teamwork-in-america

xvii. Abudi, Gina. (n.d.). The Five Stages of Project Team Development. Retrieved on October 9, 2018 from https://project-management.com/stages-of-team-development/

You must be logged in to post a comment.